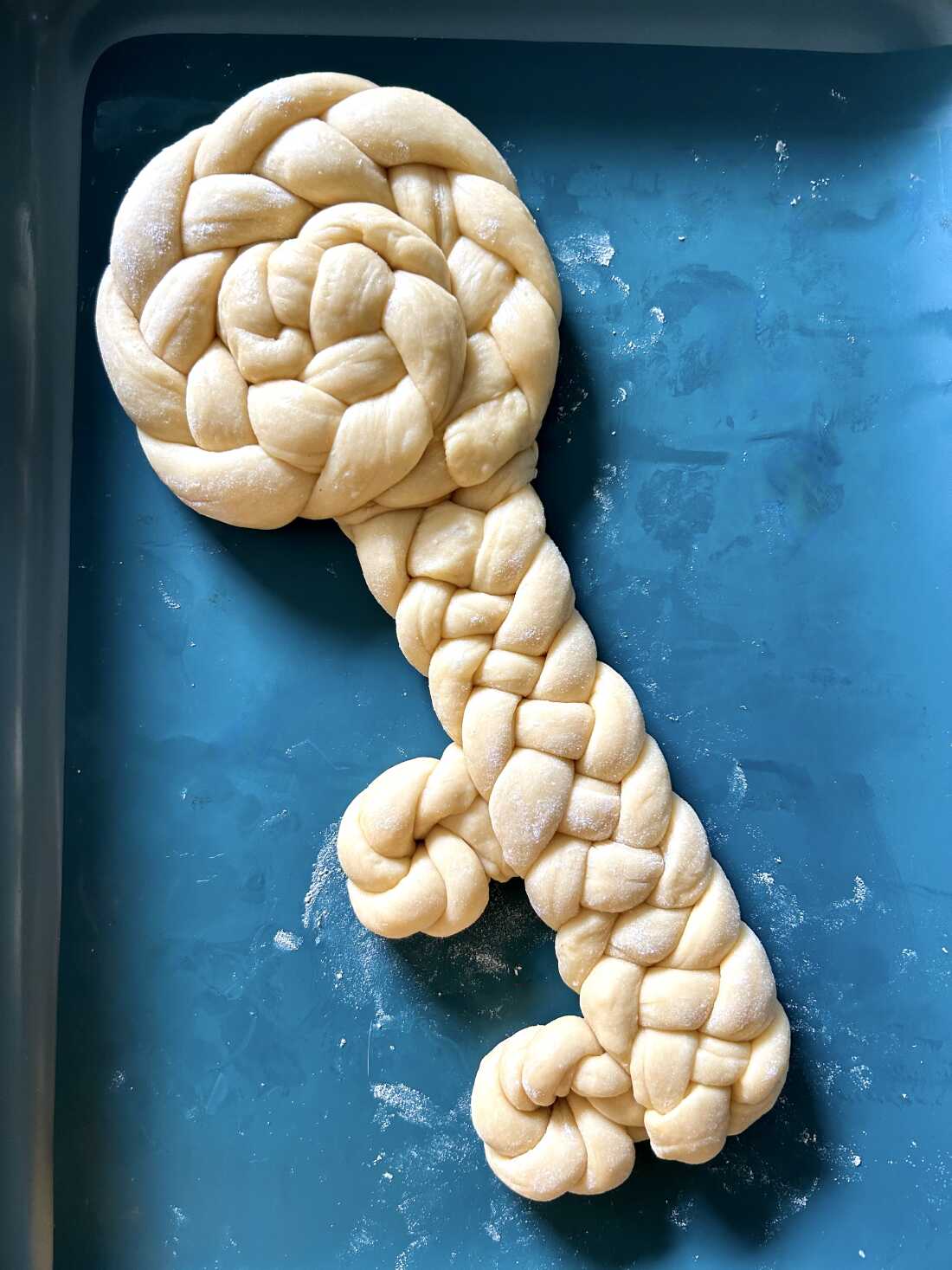

Shlissel challah is the name given to the special challah baked for the first shabbat after Passover Shprinzy Friedman/Shprinzy Friedman hide caption

Religious tradition is not handed down fully formed from God on high. It's made by people, and shaped by human factors - politics, faith, fear, geography, community. And, sometimes, how pretty something looks on Instagram. Like shlissel challah.

Shlissel challah is the name given to the special challah baked for the first shabbat after Passover. During the holiday, many Jews avoid leavened products - that means no bread, lots of matzo. It would be understandable that after 8 days of flatbread, a return to fluffy, golden loaves of challah would be a celebration. But it doesn't just stop there.

"So shlissel is Yiddish for key," explains Shayna Weiss, the sSenior sAssociate dDirector at the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies, and affiliate faculty of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Brandeis University.

"Shlissel challah is a custom that many Ashkenazi Jews have, where for the Shabbat after Passover, they bake challah either into the shape of a key, or with a key inside of the challah. And it's supposed to be what's called a segula, which is like a sort of good luck omen, for parnassa, for livelihood."

As with a lot of home customs, the origins of shlissel challah aren't super clear- like why even a key at all?

"Judaism - I should say, or some parts of Judaism - likes to think of itself as a set of practices, right?" says Weiss. "But there's always going to be a gap in what is sort of set out in a book, and what academics call mimetic practice, or sort of daily or lived practices."

Weiss says this particular home practice comes from the Orthodox tradition, likely in the 19th century, and there may be some parallels to other bread traditions. But this old tradition is perfect for the current social media moment.

Search the hashtag online, and you will see examples from rustic to ridiculously ornate, from home bakers and Orthodox "challah influencers." Some are lumpy and misshapen, some are crafted of intricately swirled braids of all sizes, some look like they could unlock a magical yeasted fairy house. And you'll find many people baking shlissel challah not because they grew up with this tradition, but because they saw one of these beautiful pictures online.

If you want a 'gram-worthy shlissel challah, there are a few tips. Sonya Sanford is a chef, food writer and podcast host who has taught challah workshops (and whose cookbook happens to be called Braids).

Sanford says you can use any challah recipe, but make sure your dough is relaxed enough to work with (if it wants to shrink back, just cover and set aside for a few minutes), and roll out your strands longer than you want the finished loaf (to account for the length you'll lose in braiding). And, most importantly, let it rise fully before baking.

"One of the things that people often ask me is, 'why is my challah splitting? Why don't my braids look good together?'" says Sanford. "And it's usually because you haven't let your challah rise for long enough during the second rise. That's particularly important with a shlissel challah, because you want it to hold its key-like shape. So if you pop it in the oven too early, it might split and break apart."

Sanford also favors brushing the loaf with an egg wash twice for a beautifully golden key- once at the beginning of rising, and then a second time right before it hits the oven.

Shlissel challah in dough form, before it's baked. Sonya Sanford hide caption

With this parade of beautiful loaves and hashtags, it's easy to wonder - is this a religious practice? Or a social media performance? Professor Shayna Weiss says the answer might be ... yes.

"I think any time you put something on Instagram, it's a performance. And of course raises the question, right? Like, if you make a shlissel challah and you don't take a picture of it, right, does it even count?" laughs Weiss. But she says something can be both a performance, and an authentic practice.

Weiss says shlissel challah can be just as real as any other ritual. And while Sephardic families have a ceremony